New Transcranial Stimulation Study in Southern California Seeks IC/BPS Patients

With the now universal acceptance that many IC/BPS patients struggle with widespread pain (myself included), the central nervous system has become a new therapeutic target. Understanding how the brain and nerves influence pelvic pain and muscle health is the focus of Dr. Jason Kutch’s work at the University of Southern California. A biomedical engineer with a PhD in Applied Mathematics, Dr. Kutch began experiencing chronic pain while in graduate school and understands, implicitly, the trauma that pelvic pain can cause. With that experience and a motivation to help other sufferers, he is leading the IC research community into the study of neuroscience. Patients who struggle with chronic overlapping pain conditions will find comfort in his story, insight into the brain and brain function and, most importantly, new potential treatments that may help calm the nervous system. We are delighted to share an interview with Dr. Kutch. Much of our work in 2023 will focus on educating both patients and providers of the role that the nervous system can play in the symptoms of IC/BPS and why mind-body medicine should be incorporated into the IC/BPS widespread pain treatment.

What is neuroscience?

Neuroscience is the study of how the nervous system works. It can range from studying how nerve cells operate and communicate with molecules all the way up to the underpinnings of human experiences like pain.

As an engineer and mathematician, how did you become interested in neuroscience?

I was always fascinated by how the brain coordinates complex human movement, but I also wanted to study engineering because there is something so satisfying about designing something, working out the equations, and then going to the shop and actually building it. I worked in my senior thesis on building a robot arm with these muscle-like motors controlled by an artificial neural network. Trying to build robots that mimic human movement gives a great appreciation for the human brain.

Your history is very compelling as you, too, struggle with pelvic pain? What triggered that for you?

About a year into my graduate studies in neuroscience and mathematics, I suddenly developed very bad headaches that couldn’t be explained. A few years later, unexplained low back pain started for me. And toward the end of my graduate studies, I developed pelvic pain. In each case the triggers were hard to identify though I suspect that riding a bicycle to work may have played a role in my symptoms.

What role does the brain play in pain processing and muscle tension?

Pain and movement (which happens through muscle tension) are fundamentally linked. Usually pain is the feeling we get when we have a strong desire to move away from something to protect our bodies or to not move while we allow our bodies to recover. Some of this driven by the spinal cord, that has nerve cells that very quickly pull your arm away if you accidentally touch something hot. But your brain has lots of links between pain and movement too. The links in the brain are probably more related to higher-level processes like prediction and planning – like how should I plan to move my body differently today if I injured myself and anticipate pain.

Patients may be upset to learn that their brain is playing a role in their symptoms? Does this suggest that they are mentally ill?

I struggled with this question myself. I ultimately came to an understanding that pain is the combination of something real happening in the body and how the brain is processing it. I like the analogy of an electric guitar – the sound you hear is a combination of how hard the string is hit (body) and how dialed up is the amplifier (brain). Medical doctors can use tests to help us determine if what’s going on in the body is objectively a problem. It is common in people with chronic pain, including myself, to have very normal test results. So in that case, I’m okay with the idea that my brain is playing a role because it gives me more of a sense of control over my symptoms. And because of this sense of control, I don’t personally find the mental illness label useful for my pain.

You chaired the neuroimaging working group in the MAPP research studies. What did that work reveal with respect to bladder specific symptoms vs. patients with systemic pain?

Our research showed that there is a big difference in how the brain processes pain between patients with more bladder/pelvic-specific symptoms and those patients who in addition have widespread body pain. Those with more widespread pain have differences in function in areas that regulate sensation and movement. These areas are even growing slightly larger in these patients. We’re still working on new studies and more extensive data to dig into this further, but I suspect that information from the body is getting processed differently in people like me that have widespread body pain.

One of your recent studies found that men with chronic pelvic pain have trouble controlling their pelvic floor muscles, that they aren’t relaxing as they should. Could that be happening in bladder centric patients too?

We were excited about this study because it was the largest study I know of that made objective measurements of pelvic floor muscle function in men with chronic pelvic pain. It was interesting because the resting activity in pelvic muscles looked similar between men with pain and men who didn’t have pain, but after a few voluntary pelvic floor contractions, the resting activity went way up in men with pain, particularly those that had pain after sex. We don’t know if the same thing happens in women with pelvic pain or in bladder-centric patients, but we hope to learn more in future studies.

What happens when someone can’t relax their pelvic floor muscles completely?

No one knows for sure. There is an idea that this has the potential to seal off the urethra and trap urine or semen near the prostate in males. It may also simply give an uncomfortable sensation of a muscle suddenly being tight, or interfere in some other way with regular bowel or bladder function and therefore be interpreted by the brain as pain.

Which comes first? A change in that region of the brain that controls muscle tension or does the dysfunctional muscle change the way the brain responds??

Dr. Chelsea Kaplan at the University of Michigan has been working to understand the emergence of widespread pain in adolescents. One of her first studies in this area found similar changes in sensation and movement regions of the brain that we found in adults with widespread pain. Interestingly in adolescents, these brain changes were observed before the adolescents started reporting pain. So a lot more work to be done in this area, but we think that some of the brain changes may be preceding the development of pain.

How does pain expand from being localized, to regional and then systemic?

It is an interesting question that I have thought about, but there isn’t enough good data. In MAPP, it was interesting that patients with more widespread pain did not report having pelvic pain symptoms for any longer on average than those with more bladder-centric pain. This suggests that a person can remain stable over time with bladder-centric pain without progression to more widespread pain. And to my knowledge, the common overlapping pain problems like headache and low back pain do not appear in any particular order.

Are patients with multiple/overlapping pain conditions a distinct patient group separate from patients with Hunner’s lesions? Do they require different treatment modalities?

Henry Lai and colleagues found in MAPP that indeed patients without Hunner’s lesions tend to have more widespread pain, and those with Hunner’s lesions tend to be older with more urinary symptoms. Best treatment approaches are still unknown.

What is transcranial stimulation?

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, is a way that you can non-invasively stimulate the brain. It uses a device resting on the scalp to deliver brief pulses of magnetic energy which pass through the skull and modulate the activity in nerve cells.

Why would transcranial stimulation of the brain reduce pelvic pain and discomfort?

We’re studying how TMS might reduce chronic pelvic pain, both more bladder-centric pain as well as widespread pain. As in most studies of TMS for pain, we are stimulating regions that control movement, since stimulating those regions interestingly seem to give the greatest pain relief. We hope that our study will have a big impact on the field, since we are scanning the brain before and after the stimulation. We will be able to find out if TMS is reducing pain by improving how the movement circuitry works, or if it reduces pain by indirectly activating deeper parts of the brain that reduce pain, like the periaqueductal gray.

Does it change the brain permanently? Adverse events?

In clinical use of TMS for depression, there is evidence that multiple repeated treatments with TMS may produce remission of depression symptoms in some individuals. In our experience and in the literature, the most common side effect is a transient headache.

Do you believe that a “disease process” is driving central sensitization and the development of widespread pain?

I think that central sensitization is a process by which the nervous system is interpreting the environment as threatening and storing that information to better protect itself. Why this causes pain in some individuals and not others needs further research.

What role does the salience network play in our brain? How has it changed in patients with COPC’s.

The salience network is believed to be important in processing information from many sensory systems and determining what is most important for attention. Adults with COPCs (as well as the adolescents that go on to develop widespread pain, mentioned above) seem to have some parts of the brain that represent the body overly connected to the salience network. The implication that we need to test is whether this is causing people with COPCs to pay more attention to particular areas of their body.

Can the brain trigger a “flare?”

We know from a few studies that TMS to the brain can mitigate the intensity of the pain resulting from a pain-producing stimulus to the body. So my thinking is that flares in patients with chronic pain may be caused by events in the body, but worsened by processing in the brain. We’re looking to test this further, because I am excited about the possibility of using a session or two of TMS occasionally to help patients get over flare-ups faster.

What has worked well for you as a pelvic pain patient? How do you cope on a daily basis when pain gets triggered?

What has worked well for you as a pelvic pain patient? How do you cope on a daily basis when pain gets triggered?

If I have a pain flare-up, I try to go surfing as soon as I get a chance. I figured out a few years ago that not only did surfing make pain go away immediately, but also that it made it less likely for me to have pain even on days when I was not surfing.

Surfing is a full body sport in a dynamic environment. Surfing engages all of my senses. By focusing on something outside of the body, this may change the way that the salience network and pain perception functions. Other activities that are really engaging may produce similar benefits.

I’m starting up a research project now to look at this in pelvic pain patients, as well as to develop a virtual reality surfing environment so this benefit might get to more people even if they don’t have ocean access.

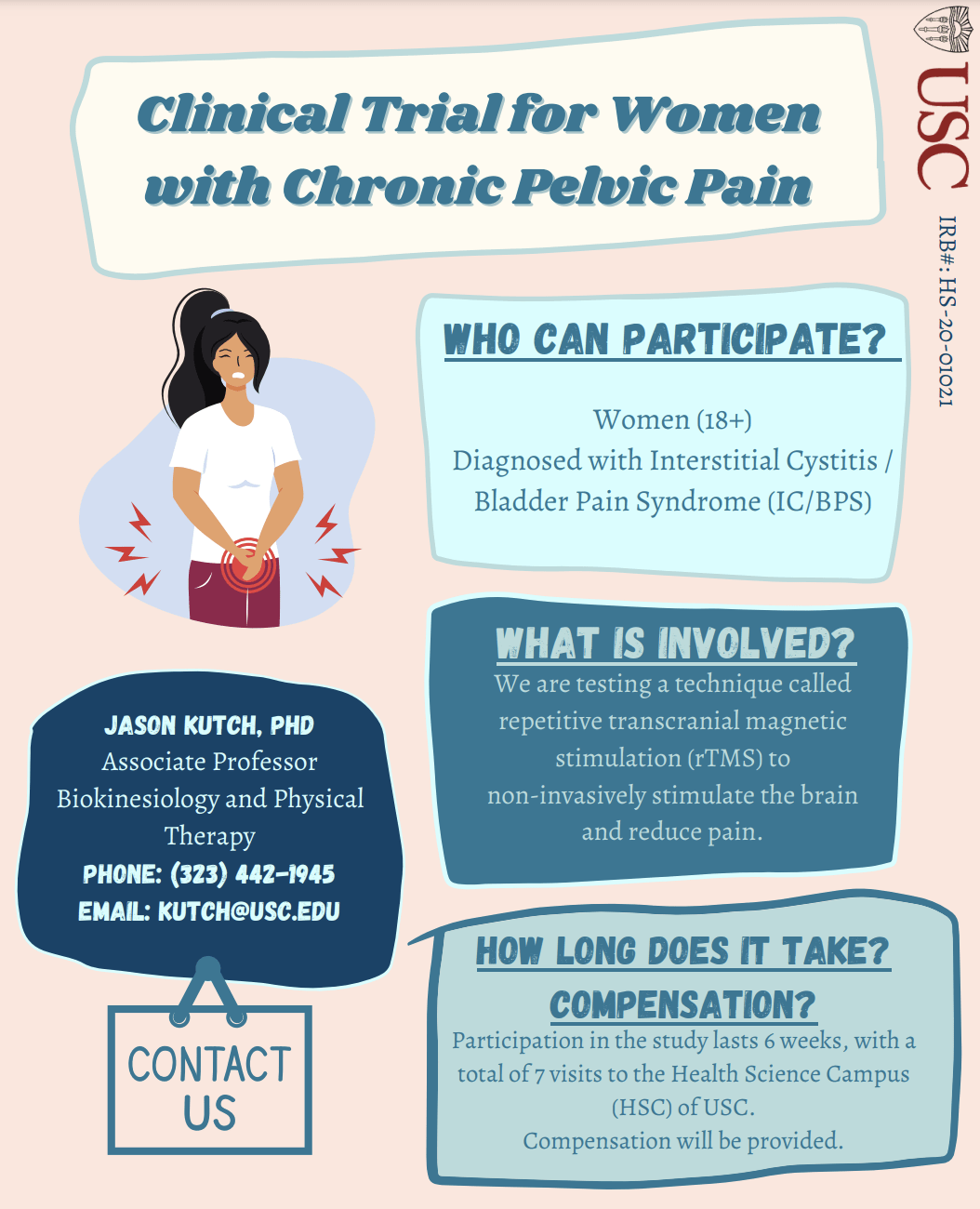

A New Study Using Transcranial Stimulation

Dr. Kutch is currently seeking IC/BPS patients to participate in a new transcranial magnetic stimulation study, aka ICBrainStim. His previous study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to compare women with IC/BPS to those without. It found that women with IC/BPS had altered resting activity in supplementary motor area (SMA) of the brain shown to control pelvic floor muscle activity. They hypothesize that this may be evidence of an important theory of chronic pain: that motor cortical changes occur that are initially beneficial to increase protective muscle activity but are ultimately maladaptive and perpetuate pain. If this theory is true, it should be possible to reduce pain and muscle activity by improving brain activity.

His new study will use non-invasive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) directed at pelvic-SMA to determine if it can reduce pain, improve resting brain activity (fMRI) and resting pelvic floor muscle electromyographic (EMG) activity in IC/BPS, and to link the pain reductions to fMRI/EMG improvements to develop a causal mediation model of IC/BPS symptoms.

They hope to recruit 50 women with IC/BPS to participate in the study, and participants will be randomized to 2 groups of 25: high-frequency (active) or sham (inert). Preliminary data suggests that high-frequency stimulation is the best stimulation protocol for reducing pain and improving pelvic-SMA activity and resting pelvic floor muscle activity.

For more information, please visit their study website at:

https://sites.usc.edu/ampl/projects/