(By Jill Osborne) The long awaited new clinical guidelines for the treatment of interstitial cystitis (aka bladder pain syndrome) were released by the American Urology Association (AUA) this month, offering what may be the most comprehensive clinical care article written to date in the USA. Solidly written, it offers new insight into diagnostic testing as well as a new, six stage IC treatment algorithm that can be used by physicians and patients as you consider your treatment and pain management plans.

Please help us share this vital new resource by printing both this summary and the guidelines out to share with all of your medical care providers.

Please help us share this vital new resource by printing both this summary and the guidelines out to share with all of your medical care providers.

What is an AUA Guideline?

With its mission of improving the knowledge of urologists around the USA, the AUA occasionally releases documents that assist urologists in the diagnosis and treatment of various urologic diseases. We are thrilled that they devoted almost two years to the creation of a new set of guidelines for interstitial cystitis. They are intended to instruct clinicians and patients how to recognize IC/BPS, make a valid diagnosis and evaluate potential treatments.

Why is it important?

Have you ever had a physician tell you that there were no treatments for IC or a family member who said that IC was a figment of your imagination? How about a physician who refuses to provide pain care? This document provides desperately needed education for medical care providers, patients, family members and the community at large.

Who drafted it?

In 2008, the American Urology Association convened a diverse panel of more than a dozen IC researchers and medical care providers to draft the guidelines. The effort was led by panel chairman Phil Hanno MD (Univ. of PA). An additional 84 peer reviewers reviewed the final document before it was approved by the AUA Board of Directors in January 2011. None of the participants were compensated by AUA for their work.

How was it created?

The panel performed a systematic review of IC research studies published from 1983 through July 2009. Using this research “evidence” as well as “clinical principles” and “expert opinions” offered by the panelists, the guidelines consist of 27 statements to guide a patient through diagnosis and treatment.

What’s their definition of IC/BPS?

They chose to use the definition first established by the Society for Urodynamics and Female Urology.

“An unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.”

Is IC more than just a bladder disease?

Citing several studies which explored the related conditions found in IC patients, the authors explored several theories, one of which is “IC/BPS is a member of a family of hypersensitivity disorders which affects the bladder and other somatic/visceral organs, and has many overlapping symptoms and pathophysiology.” IC could be a primary bladder disorder in some patients and yet, for others, may have occurred as the result of another medical condition. The answer remains elusive.

Symptoms

The guideline emphasizes pain as the hallmark symptom of IC/BPS, particularly pain related to bladder filling. Pain can also occur in the urethra, vulva, vagina, rectum and/or throughout the pelvis. Urinary frequency is found in 92% of patients with IC/BPS.

Urgency is an often debated symptom because it is the primary symptom of overactive bladder, a condition often confused with IC. Yet, the authors make a critical distinction. Patients with IC experience urgency and then rush to the restroom to avoid or reduce pain whereas patients with OAB experience urgency and rush to the restroom to avoid having an accident or becoming incontinent.

Diagnosis – Hydrodistentions No Longer The Standard

The authors urge clinicians to perform a thorough history and physical examination of the patient. Symptoms should be present at least six weeks in the absence of infection for a diagnosis to be made. A physical examination of the pelvis should be conducted for both men and women and “The pelvic floor should be palpated for locations of tenderness and trigger points.”

Several conditions should be ruled out, including bladder infection, bladder stones, vaginitis, prostatitis and, in patients with a history of smoking, bladder cancer. Additional testing, however, should be weighed with respect to their potential risks vs. benefits. They offer “In general, additional tests should be undertaken only if the findings will alter the treatment approach.” Cystoscopy and urodynamics, for example, are to be considered if a diagnosis of IC is not clear. The authors do note that cystoscopy helps to rule out other conditions which can mimic IC symptoms, such as bladder cancer or stones.

The presence of Hunner’s ulcers on the bladder wall will lead to a diagnosis of IC however the finding of glomerulations on the bladder wall during hydrodistention with cystoscopy is often vague, variable and consistent with other bladder conditions, thus the panel suggests that “hydrodistention is not necessary for routine clinical use to establish a diagnosis of IC/BPS.” Hunner’s ulcers are described in an acute phase “as an inflamed, friable, denuded area” or in a more chronic phase “blanched, non-bleeding area.”

Pain Management

The guidelines are extremely proactive when it comes to pain acknowledgement and management. The authors offered “Pain management should be continually assessed for effectiveness because of its importance to quality of life. If pain management is inadequate, then consideration should be given to a multidisciplinary approach and the patient referred appropriately.”

Pain management can include the use of various medications, physical therapy and/or the relaxation of tense, painful muscles, biofeedback and a wide variety of other options. The guidelines encourage physicians to refer patients to other pain specialists if they are unable to provide an effective pain management strategy.

Treatment Goals & Principles

The improvement of patient quality of life is the key goal of therapy and consideration should be made for a treatments invasiveness, potential adverse events and the reversibility of a treatment. As a rule, the panelists suggest that treatment should begin with generally safe “conservative” therapies. If no improvement is found, “less conservative” treatments that may have more risk of side effects and adverse events can be explored. Surgical treatment is rarely suggested and only under specific circumstances because it is irreversible.

-

Grade A = have well-conducted clinical trials and/or exceptionally strong observational studies.

Grade B = have clinical trials that have weaknesses in their procedures or generally strong observational studies.

Grade C = have observational studies that are inconsistent, small or have other problems which could influence the data.

Specific treatment choices should depend upon the patients current symptoms, patient preference and clinician judgement. In addition, it is not unusual for patients to be using multiple, concurrent treatments. If patients have not shown improvement in their symptoms after multiple treatments, the panelists suggest that the diagnosis of IC should be revisited to determine if another underlying disorder (i.e such as pudendal nerve entrapment, endometriosis, etc.) could be present.

The guidelines emphasize the importance of evaluation and tracking a patients progress using a voiding diary and/or other surveys. They suggest that ineffective treatments be stopped after a “clinically meaningful interval.” Only effective treatments should be continued.

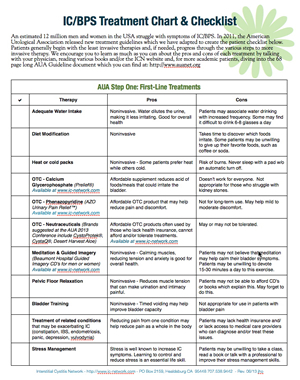

First Line Treatments – Should be offered to all patients

Patient Education – Patients should be educated about normal bladder function, what is known about IC and that multiple therapies may need to be tried in order to find symptom relief.

Self-care – Patients should learn about and avoid specific behaviors that can either worsen or give them more control over their symptoms, including: water intake, diet modification to avoid irritating foods and common flare management methods (i.e. the use of heat or cold to relax pelvic floor muscles, the use of meditation or guided imagery to reduce muscle tension, the avoidance of some exercises, tight fitting clothing, constipation treatment, etc.)

Stress Management – While stress does not cause IC, it is well known to increase IC symptoms and heighten pain sensitivity. The guidelines encourage patients to be aware of their overall stress levels. Stress management and/or better coping techniques should be practiced regularly, perhaps through use of stress management classes and/or the help of a counselor as needed.

(Editors note – A study released in early 2011 found that cats struggling with feline interstitial cystitis experienced a reduction of their symptoms and became healthier when their stress levels were reduced. This comes as no surprise to the vast majority of patients who have learned, first hand, that high stress can trigger an IC flare. Source: Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CA. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 238; 67-73, 2011. doi: 10.2460/javma.238.1.67)

Second-Line Treatments

Physical Therapy – If experience and knowledgeable physical therapy staff are available, appropriate physical therapy techniques should be used “to resolve pelvic, abdominal and/or hip muscular trigger points, lengthen muscle contractures and release painful scars or other connective tissue restrictions.” Kegel exercises and exercises aimed at strengthening the pelvic floor are NOT recommended. Why? In pelvic floor dysfunction, muscles are often too tight and kegel exercises act to increase rather than reduce muscle tension. (Editors Note – Two books are available which describe pelvic floor treatment in depth, including a variety of home exercises that can be used to resolve symptoms. Ending Female Pain by Isa Herrera PT and Heal Pelvic Pain by Amy Stein PT)

Pain Management – “Pain management should be an integral part of the treatment approach and should be assessed at each clinical encounter for effectiveness,” the guidelines encourage. With respect to the use of pain medications, such as narcotics, the authors suggest that while the risk of tolerance and dependence is possible, only rarely does addiction occur. They offer “It is clear that many patients benefit from narcotic analgesia as part of a comprehensive program to manage pain.” Yet, they also state that the use of pain medication alone does not constitute a sufficient treatment plan. Pain management should be just one component of treatment.

Oral Medication Options

Amitriptyline (aka Elavil) has several studies reporting strong success in reducing IC symptoms yet side effects were highly likely with the potential of disrupting a patients quality of life, particularly sedation, drowsiness or nausea. Side effects were the primary reason why patients stopped using the medication. Grade B

Cimetidine (aka Tagamet) acts to inhibit acid production in the stomach. Two long term studies reported that 44% to 57% of patients experienced improvement in their symptoms with no adverse events reported, making this a viable second line strategy. Grade B

Hydroxyzine (aka Vistaril, Atarax) had mixed research studies, one of which reported that 92% of patients experienced improvement yet those participating patients also had systemic allergies. Other studies found much more modest effectiveness (i.e. 23%). Adverse events were common and generally not serious. Grade C

Pentosan polysulfate (aka Elmiron), the only oral FDA approved for IC, is the most studied medication currently use with five placebo controlled clinical trials. The results were clinical significantly (21 to 56% effectiveness). Roughly 10 to 20% of patients experienced side effects that were “generally not serious.” Pentosan may have a lower efficacy in treating patients with Hunner’s Ulcers. Grade B

Bladder Instillation Options

DMSO (aka RIMSO-50), the only FDA approved bladder instillation for IC, is one of three considered a second-line therapy. Several studies were reviewed with various levels of success ranging from 25% to 90%. “If DMSO is used, then the panel suggests limiting instillation dwell time to 15-20 minutes” because longer dwell times are associated with more significant pain. Grade C

Heparin instillations have been studied using various concentrations and treatment modalities (i.e. 10,000 IU heparin in 10cm3 sterile water 3x per week or 25,000 IU in 5 ml of distilled water 2x per week) with intriguing results. The 10,000 IU study showed a 56% improvement at 3 months, whereas the 25,000 IU study showed a 72.5% improvement at 3 months. No placebo controlled studies have been done. Adverse events were infrequent and apparently minor. Heparin is frequently combined lidocaine to create an instillation popularly known as a “rescue instillation.” Grade C

Lidocaine instillations have also been studied in various dosages, cocktails and/or treatment schedules. The guidelines include several formulas for various cocktails that can be used, often including sodium bicarbonate, heparin, lidocaine and/or triamcinolone. Adverse events were typically not serious, earning this treatment option a Grade B.

Third-Line Treatments

Hydrodistention with cystoscopy may be considered if first or second line treatments have no provided relief. The panel ONLY recommends low-pressure (60-80 cm H2O) and short duration (less than 10 minutes) procedures to reduce the risk of bladder rupture. Grade C

Hunner’s ulcers can be treated with fulguration (laser or electrocautery) and/or by injection of triamcinolone into the ulcer . One observational study reported 100% pain relief and 70% reduced frequency from 2 to 42 months after heat treatment. Laser studies showed similar effectiveness however, in both cases, ulcers may require additional treatment. One triamcinolone treatment reported that 70% of patients experienced a sustained improvement over 7 to 12 months. Grade C.

Fourth-Line Treatments

Neuromodulation is not FDA approved for IC treatment but has been used for the treatment of frequency urgency. Neuromodulation can occur at the sacral or pudendal nerve with studies confirming that pudendal stimulation appeared to provide greater symptom relief. Long term follow up data is not available. Grade C

(Editors Note – We’re stunned to see the panelists conclude that adverse events related to neuromodulation appear to be minor and this is the one area of the report that we strongly disagree with. A review of the FDA MAUDE database for adverse events reveals hundreds of severe complications ranging from MRSA infection, difficulty walking, device malfunction and, in the past two years, more than a dozen reports of fatality. We will be inquiring of the panel if they are aware of this federal adverse event data.)

Fifth-Line Treatments

Cyclosporine A is an immunosuppresant that has been studied in two small trials with IC patients with solid results. One study compared CyA with pentosan and reported a 75% improvement in patients using cyclosporine, as well as a 50% decrease in frequency. The results of two additional studies found sustained pain relief that lasted one year or longer. Unfortunately, there is potential for more severe adverse events, including immunosuppression, nephrotoxicity, high blood pressure, increased serum creatinine and others. Grade C

Botulinum Toxin (BTX-A) injections into the bladder may be considered if other therapies have not produced improvement, however “the patient must be willing to accept the possibility that intermittent self-catheterization may be necessary-post treatment,” often for several months. BTX is not appropriate for patients who cannot self-catheterize. Grade C

Sixth-Line Treatments

Surgical intervention, such as urinary diversion, substitution cystoplasty or cystectomy, may be considered for patients who have found no relief with all other therapies and/or have developed a severe, unresponsive, fibrotic bladder. “Patients must understand that symptom relief is not guaranteed. Pain can persistent even after cystectomy, especially in non ulcer IC/BPS.” Patients with small bladder capacities under anesthesia and the absence of neuropathic pain appear to have a better response to surgical treatment. Grade C

Discontinued Treatments

The panel suggests that the following treatments should not be offered due to the lack of effectiveness found in studies and/or the risk of serious adverse events. In these cases, the risk appears to outweigh the potential benefits.

Long-term oral antibiotics

Intravesical Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG)

Intravesical Resiniferatoxin (RTX)

High pressure, long duration hydrodistentions

Systemic glucocorticoids